Padilla at home (Photo Zed Nelson/GQ/Condé Nast 2012)

It was the last bullfight of the Spanish season, held, as it has been for centuries, in the 250-year-old plaza de toros in Zaragoza in north-eastern Spain.

Juan José Padilla, a 38-year-old matador from Andalusia in the south, was fighting the fourth bull of six (he’d also fought the first.)

The bull, ‘Marqués’, was a 508kg (1,120lb) toro bravo born 5 years and 8 months previously on the ranch of Ana Romero, also in Andalusia. Before entering this ring it had lived wild, ranched from horseback, and had never before seen a man on the ground.

Padilla passing a bull with the magenta and gold two-handed capote, ‘cape’ (Photo: Alexander Fiske-Harrison)

Padilla was midway through the second of the three acts of the spectacle. He had already caped the bull with the large, two-handed magenta and gold cape, the capote, then the picador had done his dirty work with the lance from horseback, tiring the bull and damaging its neck muscles to bring its head down.

Now Padilla, rather than delegate to his team as other matadors do, was placing the banderillas himself, the multi-coloured sticks with their barbed steel heads. He had put in two pairs and was on the third. He ran at the bull with a banderilla in either hand, it responded with a charge, Padilla leapt into the air, it reared, he placed his sticks in its shoulders and landed.

Juan José Padilla ‘places’ the banderillas (Credit: WENN US / Alamy Stock Photo)

Running backwards from the charging bull, his eyes were focused on the horns coming at him in an action he had performed tens of thousands of times before. However, this time his right foot came down slightly off centre and in the path of his left, foot hit ankle, and then he was down.

In a breath the bull was on him and its horn took Padilla under his left ear, cracking the skull there, destroying the audial nerve, and then driving into the jaw at its joint. It smashed up through both sets of molars and ripped through muscle and skin before exploding his cheek bone as surely as a rifle bullet, stopping only as it came out through the socket of his left eye – from behind – taking his eyeball out with it, shattering his nose and then ripping clean out of the side of his head.

There is an image I will never lose, much as I wish I could. It is of a man standing with half his face held in his right hand. Cheek, jaw and eyeball, like so much meat, resting in his palm as he walked towards his team uncomprehending, and they, with looks of absolute horror, grabbed his arms and rushed him to the infirmary of the ring.

The second worst image

And yet here, in the amongst the carnage inflicted on a human body by a half ton of enraged animal, is the key to Juan José Padilla. The clue is in the phrase “stood up.”

Soccer players are stretchered off the field from a tap to the ankle. Boxers go down from a padded glove. This was more than half a ton of muscle, focused into a pointed tip that ploughed through his skull like a sword through snow. And the man got up and walked.

Then came coma and intensive care and surgery after surgery.

Then, as though by some miracle, ten days after the incident, Padilla was wheeled out, still unable to walk, for a press conference. In a massively slurred voice, he thanked his surgeons, God – the Catholicism of southern Spain makes Rome look agnostic by comparison – his family and friends, and the support of the world via a remarkable international Twitter campaign, #fuerzapadilla, ‘#strengthpadilla’ – undoubtedly a first for a bullfighter – for giving him the will to survive the most horrendous non-lethal injuries inflicted on a human all doctors involved had ever seen.

* * *

Padilla is a friend of mine. When I first moved to Spain in ’08 to research my book Into The Arena, I was against bullfighting but went with an open mind. Despite these misgivings, I formed an immense respect for the men who fight bulls, and Juan was the first one I met. It was he who convinced me to enter the ring myself and he has saved my skin more than once since.

AFH & Padilla with a young bull in 2009

So, when he got out of the wheelchair and turned up back at a bullring, I was among the first to know. Not least because it was the ranch he had taken me to the first time I ever got in the ring, Fuente Ymbro, also in Andalusia, where so many of the great bull-breeding ranches have been since the descendants of Christopher Columbus himself, the Dukes of Veragua, bred their fighting cattle there.

It was less than three months since the accident, but there were risks. Always ‘matador thin’, Padilla was still unable to eat solid foods and so was down to 98lbs of sinew hanging on his five-foot ten skeleton. There were psychological worries. Finally, there the loss of half his visual field and his ability to gauge distance.

He was given a couple of two-year-old, 200kg (440lb) young bulls to cape without killing and, although those watching were terrified, Padilla was calm and proficient, apparently unlimited by his various afflictions. As one mutual friend later said to me: “it was extraordinary. I have never seen so much fear around a ring, especially a private one with only experts watching, and yet all of it was ours, the audience’s. He had none himself.”

I wondered at that. I will always remember the words Padilla once said to me late one night at his house, after too much Dominican rum and Nicaraguan cigars: “My English brother, no man is as strong as he looks or as weak as he feels.”

Padilla & AFH at his home (Photo: Nicolás Haro 2009)

A fortnight later Padilla went public, announcing his return to the professional ring at the spring fair of Olivenza, the opening of the Spanish bullfighting season, with full size four and five-year-old bulls (the ages of bulls for a bullfight is enshrined in Spanish law as between four and six.)

The press loved it. The story was larger than just Padilla, superhuman as his recovery was.

The plaza de toros of Barcelona, the last remaining bullring in the eastern Spanish region of Catalonia, had closed its doors a fortnight before Padilla’s terrible injury and a spiritual link had been forged between the two in popular consciousness. The fates of the world of bullfighting and the matador widely known as its bravest – if not its most artistic – bullfighter were intertwined. Both were gravely injured, both were arguably overdue retirement. This was precisely why Padilla had announced that he would return with the return of the bullfight to Spain in the spring, less than six months after half his head had been ripped off.

The press even latched onto the traje de luces, the ‘suit of lights’, he was to wear. It would be green symbolising Spring and embroidered with the victorious laurel leaves of Roman gladiators in gold thread and hand stitched by the greatest tailor of toreros, Justo Algaba of Madrid.

The importance of the Barcelona ban was perhaps overstated. There had only been 18 bullfights in that bull-ring in 2010 when the vote was held, the rest of Spain having 1,706. Many Catalans don’t like bullfighting because they don’t like Spain, which is why three quarters of votes in favour of the ban were cast by Catalan separatist parties.

However, it still gave the story an appeal which reached across borders and oceans. I became an impromptu press agent for my old friend and teacher, dealing with the English-speaking media as the main source for information on him was the first edition of my book.

Eventually, Condé Nast commissioned me to return to Spain to cover what looked to be the comeback of the century for GQ magazine. I made the necessary arrangements.

* * *

Arriving in Spain my first destination was where the bulls Padilla was going to fight are bred, the ranch of my friends the Núñez del Cuvillo family. These are the most aggressively ‘noble’ of bulls, meaning they are quick to charge, and when they charge, they do so with nothing held back: straight, true and unflinching. Counter-intuitively this allows the more skilled matadors to work closer to the horns, as the bulls are more predictable than a bull that feints, bobs, weaves and searches for the man behind the cape. This is even more true with the smaller one-handed red cloth of the muleta used in the third and final act of the bullfight.

With this sort of bull the matador will build a series of ‘passes’ to form an intricate and emotional faena, a ‘work’, hopefully one of Art.

It’s worth noting here that for the Spanish (and Portuguese and French and Latin Americans), bullfighting has nothing to do with sport; it is described in terms of art and technique and is written about in the cultural pages of the newspaper among theatre and ballet rather than soccer and tennis. It is best described overall as a tragic drama ending in a ritual sacrifice.

There is nothing ‘fair’ or ‘sporting’ about it, nor is there meant to be, the bull’s meat has been pre-sold when it enters the ring, all rings being EU registered slaughterhouses. In fact, it is only due to the limitations of the English language that we speak of bull-fighting at all. The historic origins of la corrida de toros were indeed gladiatorial, but the reason it survived the 20th century when its practitioners perfected their techniques such that any matador could kill any bull, was that it became aestheticised: meaning they had to fight and kill with beauty.

Each ‘pass’ with the cape and muleta was named and codified, a ‘dance-book’ of hundreds of such passes was formed, and one had to execute them perfectly with a dance-partner who neither knew nor cared about the dance but was simply trying to kill. One had to then link the passes with one another in sequences in such a way that was both pleasing to the eye and moving to the emotions.

To this purpose top matadors employed movement instructors, dance teachers and artistic advisors all studying footage of them and other bullfighters going back to the origins of film itself.

Feet together, legs locked, at 90 degrees to the angle of charge, muleta held in two hands, one behind the body and one in front, José Tomás, performs a perfect manoletina, as created by the matador, Manolete, who was killed by a bull in 1947. Note how Tomás does not even look at the vast surging animal as it rears through the red cloth of the muleta inches from him, embodying two of the central aesthetic concepts of toreo, elegance and nonchalance (Photo: Alexander Fiske-Harrison, 2009)

The risk of injury and death for the man is always there, but it is the background music.

Spanish matador José Tomas stands after being multiply gored by a bull during a bullfight at Los Califas bullring in Cordoba May 28, 2008. REUTERS/Javier Barbancho (SPAIN)

The greatest artist in the ring today, José Tomás, is not paid €1m ($1.1m) an afternoon for anything other than how beautifully he fights. If one wanted mere blood and danger, one could go an see any novice matador learning his craft in the ring for free. However, as Hemingway put it so well:

“Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter’s honor.”

Returning to the ranch: the six bulls for the corrida I was due to watch had already been separated, their horns covered to prevent them from injuring one another and were relaxing in their paddock. They had been brought into the enclosures from the 7,000 acres of forest and wild meadows prior to transportation. Out in the background I could make out some of the other 2,000 cattle they had moving in herds among the oak-stubbled hills.

Whenever I have my doubts about the blood and brutality of killing cattle in this way – the bulls eventually end up as meat, leather, gelatin etc. like the rest of the 1.4 billion strong global bovine herd – I think of ranches like this with one tenth the number of cattle per acre a British farm has, and the bulls living three times as long. (Let us not mention the 78% of the 35 million cattle killed a year in the US after factory farming.)

The forests and wild meadows of Nuñez del Cuvillo

And I also think of where they live, a wild landscape, tree-shaded against the Andalusian sun: it is a nature reserve. Of the six million acres of Spanish dehesa – wooded wilderness – around a quarter is on bull-ranches, paid for entirely by the ten-fold price premium of fighting cattle over meat cattle: a fighting bull will cost €25,000 / $27,000.

The bulls looked good. They weren’t the biggest – Olivenza is a category two plaza de toros, unlike Madrid, Seville or Pamplona – but they had fine shape, with long arcing horns and well-developed morrillos, the matrix of goring muscle over shoulder and neck which is unique to the Spanish fighting bull. It is almost what defines it; that, and the relentless aggression.

A archetypical bull of encaste Domecq, the bloodline of Nuñez del Cuvillo

* * *

The next day I drove to Padilla’s home, a little ranch in Sánlucar de Barrameda, down the road from Jerez de la Frontera, the town where he was born, as was flamenco and sherry.

The iron gates rolled back into the high walls and there he was in a light blue cashmere jumper and heavy gold watch, somewhere between Gatsby and gangster.When we embraced in the Spanish manner, it was shocking to feel each one of his ribs, but I noted his arms were different too, harder with wiry muscle: there was steel there as well as bone.

“My English brother,” he says in greeting, “It has been too long.”

“Yes Maestro, it has. How are things?”

“Too much press, before a fight it is bad. Press after a fight is good.”

We chatted as we walked around the gardens with its small bullring for training, and a bar beside of for afterwards with the sign, “Here… no problems.” I had used both to their full extent in the past.

AFH training with Padilla (Photo: Nicolás Haro 2010)

We talked about mutual friends and family. His, he says, is difficult. His brother Ósacr, an assistant bullfighter, has retired after what he saw happen to Juan – his brother Jaime was also in the profession – and none of them can understand why Juan is returning to the ring. He has fame and glory, he has money, and he has a beautiful – and young – family.

“Why Maestro?” I echo.

“Because it is what I do. By the grace of God I have been given a chance to fight bulls again, and that is what I am, a bullfighter. No feeling on Earth comes close to the sensation of passing a bull with the cape, again and again and again, of dancing with Death.”

Which is an answer with which I, who learned to be a bullfighter by his side, cannot disagree.

However, I notice strain in his voice and face when he talks about this. His wife, Lidia, as beautiful as I remember her, joins us for a moment by the pool. She looks tense as well.

We go through his house, a museum to bullfighting, with a dozen heads of bulls on the walls. There are six giant Miura bull heads in the dining room alone which he killed in a single afternoon, making the room feel crowded even when no one is there.

Upstairs is the Holy of Holies. Along one wall runs a glass cabinet whose top is overflowing with trophies, while underneath a dozen ‘suits of lights’ from great moments in his career: his alternativa when he became a full matador, his triumphs in Madrid, Seville and Pamplona.

I ask him which is his favourite, and he takes out the plainest one there: no gold embroidery, it is not the matador’s traje de luce, ‘suit of lights’, but the same cut in dark wool: short jacket and high waisted trousers.

“My wedding suit,” he says.

Also, there is my own personal favourite item in this museum, the glass-topped coffee table. Within it is a broken sword laid on a base of sand and a few other taurine accoutrements. The bull that punched its horn through his neck all those years before had done so at the exact moment his sword had severed its aorta before the blade snapped from the sudden shift in weight as Padilla collapsed.

While he was in hospital, the butcher local to the ring had dressed the carcass of the animal, dividing it into parts for human consumption and parts for animal feed and by-products. There he had found the broken blade of the sword. Being a fan of Padilla’s, he had sent the steel to the authorities of the plaza de toros, who had located the rest of the weapon. They then packaged it with sand from the ring, and returned it to its rightful owner with their compliments and he had had it placed in this presentation case which tells a story as profound as any Arthurian legend or passage from The Lord Of The Rings.

Reminded of the many times he has looked Death in the face, I ask him the question I know no one else will.

“Are you afraid?”

He looks at me for a moment as though weighing his answer between what he wants to say to me and what he wants me to write. The latter won.

AFH & Padilla (Photo: Nicolás Haro 2008)

“No more than usual.”

“When you fought a bull on the ranch, how was it different with only one eye.”

“It wasn’t.”

Something about the way he says it seems odd. I nod, hiding my doubts.

But then his children who have come back from school and the mood is broken. They try out their broken English on me as he plays with them, a tender and affectionate father. I leave him to his family and his fears.

* * *

Olivenza, a town of 12,000, sits halfway up eastern Spain on the Portuguese border. I check into the Hotel Heredero where the bullfighters stay and in the lobby I bump into the matador Cayetano Rivera Ordóñez and we discuss the weight on Padilla’s shoulders. Cayetano should know, his father was famously killed by a bull in 1984 and the fame of his grandfather Antonio Ordóñez is impossible to escape. His friend Ernest Hemingway wrote a book about him, The Dangerous Summer, and the ashes of another friend, Orson Welles, are interred at his house.

AFH with a bull of Saltillo of Enrique Moreno de la Cova (Photo: Nicolás Haro 2010)

Cayetano fears for Padilla and that fear affects him deeply. This follows a theme among all the Spanish aficionados with whom I speak. One friend in Seville, Cristina Ybarra, describes it most pointedly, being as she is from a family steeped in the world of the bulls (her husband Enrique bred the first bull I fought in public.)

“I don’t want to see Padilla fight,” she said. “It would bring the wrong feelings. The matador is meant to make you feel pride for his courage. Now, Padilla would make the maternal instincts come out. That and fear. Although I understand why he does it.”

“Why?” I ask.

“The bull does not tell the matador when it is time to retire. The matador does that for himself.”

* * *

By the time of the fight the sense of excitement and fear is simply incredible. The night air is cold, but we are so packed together in the sold-out stadium that I am sweating.

When Padilla walks in, he walks in at the head of his team – banderilleros, mounted picadors – and to his right are the two other matadors fighting that evening with their teams. Next to him the most junior in age, but currently Spain’s number one in ranking, is José María Manzanares. I had met him at the ranch when we visited the bulls. He is a stylist few can match. To his right is the unreliable genius Morante de la Puebla, psychologically troubled, and prone to giving up on bulls he doesn’t like. He is also a childhood friend of Padilla’s.

Before his injury Padilla would not have fought alongside figuras such as these, mainly because they refuse to face the sort of large, difficult bulls in which he specialized. However, now the ranks of Spanish bullfighters have opened their arms to their injured comrade.

Which is why they laugh for their friend as six thousand people give him a standing ovation for just walking into the ring. And, in a breach of tradition, they defer to him, bowing him in front of them to receive the audiences’ chants of “To-re-ro! To-re-ro!” before a bull has even set foot on the sand.

Padilla, first on as the most senior matador of 18 years’ service, waits behind the barrier as a bull is released. ‘Trapojoso’, comes in with his 480kg (1,060lbs) of jet-black muscle bunched and hesitant, wary of the new environment until he sees a flash of cape from an assistant behind a barrier off to his left and sprints straight at it, horns lowered. Another assistant does the same forty yards away on the other side of the circular ring, and the bull turns and charges across the ring at full gallop, attacking the wooden fence at the other end, its horns sending splinters flying.

Padilla walks out to meet this hurricane carrying his large two-handed magenta cape. He begins with a couple of preliminary passes with one knee bent like a lunging fencer, keeping the bull at a distance to assess its character, temperament and basics like its horn-preference: orthodox, southpaw or both.

Decisions made, Padilla rises to his full height, legs locked straight, back arched like a dancer, and slowly sweeps the cape with the bull attached to it as though by glue through three perfect veronicas, the fabric brushing the animals face on each pass as Saint Veronica wiped the face of Christ on his way to Golgotha (hence the pass’s name.)

With each pass, it comes closer, and with each pass the crowd shout olé. He follows with a remate, which in making the bull circle in on itself brings the bull to standstill. If the matador has done it right he can turn his back to the animal and walk away.

That “if” now goes through the mind of every person watching. It is then that I realise that it is going to be impossible to judge how good this performance is. We are all amazed he is doing it all, and terrified he is going make a mistake.

Then the picador on his armoured horse is brought in and the bull charges the heavy horse, but its horns finding no purchase on the great draft animal’s padded covering as the picador’s lance strikes it in the shoulders. The bull continues to push, trying to destroy this new opponent, whilst the horse, trained for this, leans his shoulder down into the bull tiring it further. The bull pushes itself onto the lance until the only thing between it and its own death is the crossbar two and a half inches from the weapon’s point.

At a signal from Padilla, the bull is lured away from the fray with a cape and the horse is ridden out as the trumpet announces the change of acts to the “third of the banderillas.”

At which point we all wonder whether he will place his own sticks. Almost no other modern matadors do this, and, since it involves calculating intersecting geometries on the run, how can you do it with one eye, especially when he had nearly died doing it with two?

However, he does them perfectly, to the music of the thirty-piece band and a crescendo of applause for each pair placed.

Then the trumpets blow for the third and final act, “the third of death”. Padilla takes up the famous small red cape, the muleta, and his sword. Then he summons two men who had been standing behind a hide in the callejón, the bullfighter’s ‘alleyway’ around the ring.

I recognise them from his wheelchair-bound interview: they were the two surgeons who had put back together his skull and his life. He dedicates the bull to them, embracing both, before walking out onto the sand and unfolding the red cloth of the muleta so it hangs on the short wooden stick within it. Then, placing the sword inside its folds, he drives the point into the fabric, holding stick and sword together so the muleta presented a metre-and-a-half wide target.

He flicks the end of the cloth at the bull to give the toque, the ‘touch’ of movement which draws the bull – they are colour-blind and respond to motion – and the bull leaps at it, allowing Padilla to draw it past him, horns flying harmlessly by.

Padilla pivots on his feet and sends another ripple down the fabric, again the bull charges past, again Padilla turns, and now the olés are coming on each derechazo, each right-handed pass, and he twists and dances, the half-ton of muscles thundering around him in the pursuit of an illusion, the man standing implacably upright besieged by a plunging and bewildered Death.

Soon the bull, which has been tiring rapidly, refuses to charge, standing its ground, judiciously conserving its strength, inviting its opponent come to it, come within the lethal range of those fine-pointed horns.

Padilla accepts the offer and uses small movements of the red muleta in his left hand to line it up so its hooves come together and its great shoulders spread. Padilla aims down the blade of his sword in his right hand, sighting down the steel like a pistol barrel for the space between the fourth and fifth rib, left of the spine, right of the shoulder clavicle, a letter-box of space between concrete-strong bone.

He pushes the edge of the muleta forwards along the sand, the bull’s head goes down towards it, and the matador, for the first and only time in the fight, charges the bull.

“The moment of truth”, as it is called, is the most dangerous moment of all. The curved sword point strikes the chink in the bull’s bone cage of armour and slides down, its trajectory towards the aorta, as all the while Padilla’s exposed body passes over and around the horns.

The sword is perfect: within a minute, the bull keels over, its great heart ceasing to beat, its simple brain shutting down. Padilla salutes it.

Meanwhile the crowd are on their feet, white handkerchiefs out, petitioning the president of the plaza for a trophy for their hero, and he is given it: an ear of the first bull since a bull took away his eye. (This is a tradition born of the old days when a triumphant matador was given the meat of the bull and the ear was the ticket to collect its carcass with when he returned from his village with a cart.)

The next two bulls are fought by the other two matadors, and fought well In another break with tradition, each matador dedicated his bull to Padilla.

When Padilla enters the ring for the second time, as he told me afterwards, he knew he had won back the trust and lost the pity of the audience.

Now to show them what he could really do.

His second bull, ‘Reposado’, is faster and lighter – in weight and colour – and Padilla walks into the middle of its charging path with his capote and drops to his knees. As the pistoning fury reachs him at 30 miles an hour, he draws drew the large cape one-handed across his body so the fabric flies out to his side of his head and the bull launches itself at the movement, horns punching home mid-flight to find only fabric and air.

In a single gesture Padilla said louder than words ever could: “I’m back!”

Then, as the bull turns to find him, he rises to his feet and began a series of five perfect veronicas, followed by two chicuelinas – a slinking move which wraps the body in the cape making the horns scrape past the man through the cloth – before finishing with a half veronica and then a spinning galleo. This is better than anything I had ever seen Padilla do before. Fear and sympathy on his behalf are now replaced with pride and exultation in the collective minds and hearts of the audience.

After the picador has done his work “reducing the bull to human dimensions” in Orson Welles’ memorable phrase, Padilla takes his first set of banderillas and invites the other two matadors to join him so they could each place a pair alongside him, an unheard-of gesture. Morante de la Puebla does this very rarely and Manzanares never. Padilla asks him if he is okay with it and Manzanares says smiling that he has no idea, he hasn’t done it “since bullfighting school”. And yet each one of them places their pair brilliantly, Padilla inevitably the best, the closest to the horns.

He then invites his elderly father into the ring, luckily not to fight. (His father, by profession a village baker, once told me at lunch of his own foray into the ring: “I heard the breath of the bull in the ring, just the breath, and I said fuck this for a job and went back to baking.”) Padilla dedicates the bull to him, the same father who had been so against Padilla’s return now tearfully accepting the honour and his son’s astonishing capabilities. They embrace, clearly emotional, Padilla’s forehead against his as he speaks too rapidly and quietly to be heard. His words to his nine-year-old daughter are clear enough as she sat with a family friend in the front row of the audience: “I love you.” (Padilla’s wife Lidia is back at the hotel, unable to face watching. Their son, too young to understand, is at home with family in Sánlucar.)

Padilla walks into the ring and gives people an exhibition of the matador he had become. While including much of his trademark jerezano flamenco exhibitionism, and the inner force to dominate even the fiercest bull, he has developed a new and more understated way of doing this which better suited these smoother-charging animals.

He takes the bull through an entire textbook of bullfighting passes, linking them together into an intricate tapestry of danger and evasion, elegance and fluidity, all the while the thirty-piece band accompanying the rhythm of his movement with the brass sounds of old Spain. He ends one of his series of passes on his knees on front of the bull without the muleta, his hands opening his jacket to the bull, baring his chest to the horns, the greatest gesture of defiance in all bullfighting.

And when Padilla kills, again brilliantly, a lone voice in the crowd sings the mournful “deep song” of flamenco as he does so. He is again awarded the ear of the bull and the evening was complete. We watch the other two matadors fight and they do beautiful things, Morante with his exquisitely uncaring trincherazos discarding the bull at his feet, Manazanares killing recibiendo which no one does outside of Hemingway stories, standing still with the sword as the bull charges you. However, it is Padilla alone who is swept up on the shoulders of the crowd and toured the ring.

Or so we thought. Soon the audience realise that the people on whose shoulders he is carried are not the usual mix of his team and his fans, but are far more famous faces taking turns to carry the Maestro. All the great matadors of Spain have been watching in the alleyway around the ring, unrecognised in country clothes with peaked hats pulled low so as not to detract from their comrade’s moment in the sun.

Now, an entire profession seems to be holding him up in the air that night so the most emotional bullfighting audience Spain has seen in half a century could applaud him. He has returned, and, part mythical hero, part symbol of Spain and her fiesta nacional, he has triumphed over impossible odds and ridiculous expectations to show that he will decide exactly when he will leave the ring.

It will not be any time soon.

©ALEXANDER FISKE-HARRISON 2012

Juan José Padilla on the shoulders of our mutual friend, bullfighter Adolfo Suárez Illana, 2012

AFH & Padilla in London in 2017

This article will form one of the new chapters in the 2nd edition of Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bullfight, out in the winter of 2023.

“The bullfighter-philosopher”

The Times

“Thrilling… An engrossing introduction to bullfighting.”

Financial Times

“An informed piece of work on a subject about which we are all expected to have a view.”

Daily Mail

“An engrossing introduction to Spain’s ‘great feast of art and danger’. Brilliantly capturing a fascinating, intoxicating culture”

Sunday Times

“A compelling read, unusual for its genre, exalting the bullfight as pure theatre.”

Sunday Telegraph

“Complex and ambitious, compelling and lyrical.”

Mail on Sunday

More about the author:

The Spectator, 16 August 2023

The Times, 5 July 2023

Mail on Sunday, 24 July 2018

Diario de Navarra, 11 July 2016

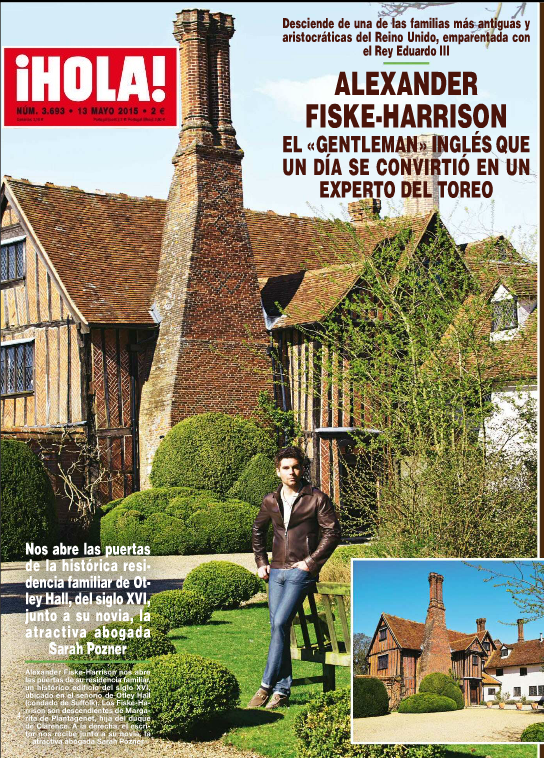

¡Hola!, 13 May 2015

ABC, 31 August 2013

Financial Times, 31 May 2013

Mail on Sunday, July 10th 2011

The Times, 6 December 2009

Written from the heart, with another level of understanding, about the bulls and the men who fight them.