When I first went to my first bullfight 25 years ago, I was 23 and was sure I would hate it. I was a passionate animal lover and had been a keen amateur naturalist since childhood, a member of the WWF (which I remain to this day) & Greenpeace, a former zoology undergraduate student at the University of Oxford, and was at the time a philosophy postgraduate at the London School of Economics and Political Science. (I am currently doing postgraduate work at King’s College, London, this time in applied neuroscience.)

It should be obvious that this is not an auspicious CV for a future aficionado a los toros.

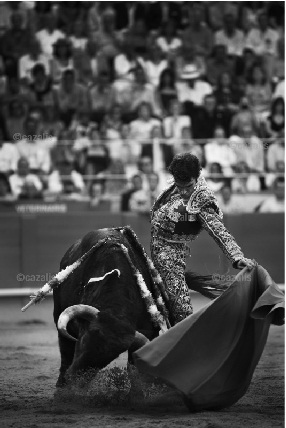

As expected, what I saw contained many moments of brutality and blood but I was surprised also to find I could see beyond them and feel moments of breathless thrill as well.

What genuinely shocked me, though, was that I could also perceive intermittently, and only with one of the bullfighters present that day, a form of beauty that was entirely novel to me.

In my moral confusion, I decided to research this alien thing, reading what I could in English – Ernest Hemingway, Kenneth Tynan, Barnaby Conrad – and going when possible to see a corrida, a ‘bullfight’, on my annual visits to Spain. Each time I went with a little more understanding and a little less aversion. Some would argue I became more sensitive to the aesthetics, others that I had become more inured to the ethics (or lack thereof.) I wouldn’t like to say either way.

Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bullfight was published by Profile Books in 2011 and shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book Of The Year Award – the oldest and richest sports writing prize in the world – the same year.

Following my essay on the subject for Prospect magazine, ‘A Noble Death‘, in 2008 I was commissioned to write a book and moved to Spain for two years. Among other researches, I trained as a bullfighter to the level of matador de novillos-toros, facing endless cattle from old, heavy and wise to young, light and fast. I ended by killing a single animal in the ring, a novillo, a three-year-old bull weighing around a third of a ton.

As part of the research, I also participated in the encierros, ‘bull-runs’, of Pamplona and ran with fear and ignorance among the masses of drunken foreigners and adrenaline seekers who fill those streets.

Unlike those visitors, I returned, and ended up running in towns across Spain, away from the tourist trail and among those born to this bloodless and less ritualised, more pagan practice. This led to my second book on los toros – as editor and primary author – with chapters by the Mayor of Pamplona, along with John Hemingway – grandson of Ernest – Beatrice Welles – daughter of Orson – and many others.

The Bulls Of Pamplona, edited by AFH and co-authored with a foreword by the Mayor of Pamplona and co-authored by John Hemingway, Ernest’s grandson, Beatrice Welles, Orson’s daughter and many others.

This makes me singular in my afición in English-speaking countries but in Spain – or Portugal, France, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela – the picture is very different.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison running with the Torrestrella bulls of Álvaro Domecq – striped jacket – in Pamplona (Photo: Joseba Etxaburu – Reuters)

According to the annual figures on asuntos taurinos, ‘taurine matters’, published by Spain’s Ministry of Culture, the bulls are on the way back for the first time since the world economy collapsed in 2008.

When I first came to Spain to research in 2007 for Prospect magazine there were 3,691 major public bullfights that year, including corridas, of which there were 953, alongside novilladas with novices, and rejoneo with horseback bullfighters.

Following the financial crisis of historic proportions the next year, there was a precipitous drop in numbers, not only for bullfighting but all expensive live spectacles such as theatre and opera. This drop evened out, averaging at a 6% annual fall until I began researching my second book in 2015, when the fall in corridas was 1% per annum.

However, after COVID-19, the number of bullfights of all kinds in total in 2022 was up 8% on 2019 at 1,546 and the number of full corridas up 18% at 412.

Now, more than ever, when the bulls are both resurgent and yet ever-more questioned as an emblem of Spanish identity, the bewilderment of English-speaking nations on the subject is not only the norm, but has become a weapon in the hands of vested interests.

Both sides in this polarised debate make things up. This was one of my greatest frustrations as a researcher for as long as I could truthfully describe myself as sitting on the fence on this issue (roughly until late 2011.) However, what always confused me was why those who are against bullfighting need to make things up in the first place? After all, everything is on display; there is no backstage in this theatre of death: the blood is there for all to see.

In terms of those bloody facts that organisations like PETA, or the League Against Cruel Sports, regard as relevant it is simple: an animal is systematically injured and exhausted for around twenty minutes and then killed in public. Surely, in the modern world, that is all one needs to say. It is down to the other side to explain why.

So, how to explain in English this utterly foreign and extravagantly violent pursuit? The simplest way is to concentrate on the bloodiest and most emblematic version of it, the corrida. However, it’s worth remarking that world of the bulls is much larger than the corrida alone. In 2022, there were 16,868 ‘popular’ bull-festivities beyond bullfighting – such as bull-running events – a number that has increased year on year since I began serious research in that particular area in 2008.

The author bullfighting on the estate of Enrique Moreno de la Cova – in the background alongside Antonio Miura – by Nicolás Haro, from Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bullfight

* * *

So, what is a ‘bullfight’?

At the risk of sounding both evasive and pedantic, originally a bullfight was the setting of dogs onto a bull, a vicious blood-sport practised by the English which had its zenith under Queen Anne in the late 1600s. It was banned in Britain under the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835. British bull-baiting is where the word “bullfight” comes from and where, interestingly, Britain’s national symbol comes from, the bulldog. Spain’s is the bull itself.

This word has been co-opted to translate the Spanish word “corrida”. However, this corrida is not regarded as a fight in Spain (and to confuse matters more in English ‘bullfight’ is also used to cover other activities, including novilladas with novices and rejoneo with horses.)

In all these events toreros, ‘those who work with bulls’, are in teams, each team following their Maestro – and employer – who in the corrida is the matador, a word which means ‘killer’, pure and simple.

“Matador de toros bravos” is a professional title and a license is issued for it by the Spanish Ministry of Culture once a certain standard of competence has been achieved which is regulated by Crown law in Spain.

In 2022 there were 803 licensed full matadors in Spain and there 10,554 licensed toreros in the broader sense of the term which includes banderilleros, picadors, mozos de espadas – ‘sword-pages’ – rejoneadors, novilleros and so on. (As a point of interest, 274 of these bullfighters were women, mostly among the horse-riding rejoneadors, although 7 of them are full matadors.)

The full phrase corrida de toros actually translates best as ‘coursing of bulls’ (coursing is hunting at a run.) Hence it is called la course des taureaux in France where it is also both popular and legal in the south. It developed from knights jousting bulls on light horse bred from the Arabian bloodlines introduced by the Moors when they conquered the Iberian Peninsula in 711 AD. However, when the French Bourbons replaced their Hapsburg cousins on the Spanish throne in 1700, they frowned on the spectacle, banning it more than once, and the nobles followed Royal example and withdrew from the ring with their horses, leaving the common man to take over on foot.

El Cid bullfighting, as described in the Poem of the Cid, composed circa 1140, here depicted by Francisco Goya (Image from Wikipedia)

In its contemporary incarnation the corrida is usually a two hour spectacle in which six bulls are danced with and dispatched in sequence, usually by three matadors facing two separate bulls each that evening.

Each individual 20 minute period with a given bull is itself sub-divided into three acts.

Those who regard it as a barbarism call this a blood-sport, while those who enjoy it call it an art, and neither camp use these terms as metaphors. I, personally, call it an art not because of my ideological loyalties, but for a cluster of factual reasons.

First, the sense of the word art being used is ethically neutral. It is not being called an art to outweigh moral imperatives, any more than people could justify wearing leather shoes and belts – for which cattle have ‘unnecessarily’ died – by saying actors wear them in theatre and film, which are also artforms. Equally, the fact that actors wear animal skins doesn’t negate acting as an artform.

Second, no one who works in bullfighting, or watches it with any degree of regularity, calls it a sport. This includes journalists: all bullfights are reviewed in all major newspapers, but in the cultural rather than the sporting sections.

Third, no one keeps score in bullfighting and there is no way for anyone or anything to win. Betting does not exist. If a matador is incapacitated or killed by the bull assigned to him, another matador takes his place, and if all matadors at the plaza de toros that day are too injured to continue – as happened at Las Ventas in Madrid in 2015, which I was asked to explain on the BBC at the time – then the bulls are still killed anyway.

The cold truth is that the bull’s meat is pre-sold before entry to the ring, which is a licensed as an slaughterhouses under European law. Indeed, in many senses bullfighting grew out of the abattoirs, mataderos, of Seville, which was where the early toreros practised their craft.

For this reason, the notion of fair play – a common cause of complaint among English-speaking audiences – has as little bearing here as it does in other theatres. The bull has as much chance as Hamlet or Macbeth of survival. It is no coincidence that one of the better books on the subject in English is Bull Fever by Kenneth Tynan, drama critic and founding literary manager for the British National Theatre.

The matador Cayetano Rivera Ordóñez by Nicolás Haro, from Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bullfight

Clearly it is not sporting then, but why artistic?

Well, for starters it is called an art in Spain, and a clutch of matadors such as José Tomás have been given the Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts by the Ministry of Culture alongside painters like Salvador Dalí, composers like Joaquín Rodrigo, filmmakers like Luis Buñuel, opera singers like José Carreras, ballet dancers like Tamara Rojo, actors like Antonio Banderas etc. Not one sportsman is on this list.

Stronger than that, though, is the argument of function. In common with all performance arts, success on the stage or the sand is directly defined by how much the audience has been emotionally moved. The morality or lack thereof is not what is at issue here: I’m not saying it is ethically justified by being an art. I’m just pointing out that to attack it for being ‘unsporting’ would be to commit a category error akin to talking about match-fixing because Jay Gatsby dies every time you read Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel.

A young or talentless matador may receive only a few hundred Euros for an afternoon, out of which he must also pay his team of three banderillos, two picadors, his sword-page and his manager’s cut.

In contrast, the phenomenon José Tomás commanded €1million for a single afternoon in Barcelona in 2009.

Both are paid out of the box-office takings, and although the empresario of the ring negotiates the fee, he does so by predicting the public’s taste and setting prices accordingly: aficionados only open their wallets if they think their hearts will be moved.

This emotional movement is not mere thrills either, otherwise novices would be paid more than veterans as they are more often in danger. The emotions a great matador engenders are infinitely more subtle than that. Which is not to say they are not at risk: 536 noted professional bullfighters have died in the ring since 1700, 3 in 2016 alone, including the matador Victor Barrío in Spain (a friend, whose death I wrote about in the British newspaper The Sun.) However, in bullfighting risk is like the music in a drama, underlying and underpinning everything, but certainly not its sole essence.

At least not any more.

When the knights were still in the plazas, and for a long time afterwards, what art there was in the spectacle was of the most primitive form. The corrida stood for Man’s struggle with Death, but also it was a man struggling with death. In that sense, philosophically speaking, it is the most basic form of art. It is a ‘form of representation’ that also is the very thing it represents. Matadors were tough, brave and athletic, wearying out the bull at the end using the muleta, the famous red cloth, to distract it along with constant nimble footwork before killing it with the sword.

The estocada, the kill with the estoque, the ‘rapier’, was the most important part in those days. However, this changed in the 20th century, and this change is usually attributed to the innovations of the matador Juan Belmonte, born in the slums of Triana, Seville, in 1892.

In order to avoid getting ahead of myself, it is worth explaining a little about the real foundation of the bullfight, though, which is the bull.

* * *

The toro bravo, or more formally toro de lidia, is the male of a particular breed of domestic cattle.

All breeds of domestic cattle are of the same species, Bos Taurus, which is in turn the same species as their four century-extinct ancestor, the aurochs. These breeds vary between one another almost as much as the breeds of dog (which is in turn the same species, Canis lupus, as its wild ancestor who remains extant, the wolf.)

The Aurochs from Vig, whose skeleton is in the National Museum of Denmark, weighed almost 1000 kg (2,200 lbs), and its shoulder height was almost 2 metres (6 feet 6 inches.)

The relation between a Spanish fighting bull and aurochs is most like that between a feral (untrained, wild-living) German shepherd and a Northern timber (Mackenzie) wolf: they are built along the same lines anatomically and morphologically, although the wolf is considerably larger, and both have ready access to the same ferocity.

In stark contrast, the most common variety of cattle in Britain and America, the Holstein-Friesian, is basically a box of meat/milk on legs and has had aggression and horns bred out of it to make handling it easier. That said, we still lose about a dozen people a year to cattle in the UK and ten times that number in the US.

The author on horseback herding the bulls of Álvaro Domecq on his estate by Nicolás Haro

(The lighter-coloured cattle are tame steers of the Red Berrenda breed used to assist ranching.)

Toros bravos are born wild – well, technically feral – on estates composed of meadow and forest. These are privately owned and box-office subsidised nature reserves. In 2022 there were 1,331 registered and licensed estates and comprising 1.3 million acres or 1% of Spain’s landmass – as Yellowstone is 1% of the US – and 17%, more than one-sixth, of its natural landscape.

In this wilderness, the herds live at a population density one-tenth that of standard, non-‘factory’ method European farms.

The end of bullfighting would be the end of these reservoirs of biodiversity as this land, which is classified as agricultural, would simply change to another form of farming. At a total land value of €1.86 billion, no conceivable Spanish government could afford to purchase and maintain this as national parkland, especially given the loss on tax income from the €3.56 billion in economic activity bullfighting generates, as well as the unemployment benefits for the 200,000 people who would lose their jobs.

All cattle from these farms – more than 200,000 – end up in the food-chain, as with the rest of 1.3 billion-head global cattle herd. This food production result is why a small fraction of the European Union subsidy for farmers in Spain goes to these ranches, not to subsidise bullfighting as some disingenuous campaigners claim and the lazier sort of journalists repeat. What is more, since 2015, not one penny of subsidy goes to those animals from the ranch – a fraction of the total – who are destined for the ring rather direct to the food/chain via the slaughterhouse.

On average the fighting bull lives in this idyll three times as long as the eighteen-month old meat-cow/bull at slaughter. It is ranched from horseback and only sees a man on the ground a few times in its life: when it is branded and the odd veterinary encounter. This means that when it enters the plaza it does not too quickly learn to distinguish the fabric lure from the man holding it. However, the downside of this is that it is very difficult to tell whether or not a bull will perform in the required manner when it enters the ring. Unlike, for example, horse-racing – a similar size industry in Britain if you discount the gambling – there are many more characteristics required of a bull than simple speed and stamina.

Due to this inbred and carefully nurtured ferality (as mentioned above, no domesticated animal breed is wild in the strict biological sense) the bulls are maintained, herded and transported with extra care – even the fencing must be specially constructed – due to the risk to humans, horses and the bulls themselves which, if they are in anyway damaged on arrival at the ring, will be rejected by the resident veterinarian there as great cost to the breeder.

During the Franco era, and immediately after, there were often accusations of the manipulation of bull-horns, particularly of shaving them, afeitado. The idea was that even a few inches off the length would make the bull less accurate. However, the inspection regime at bullrings nowadays, as with all things in Spain, is both more rigorous and more transparent. The last scandal involving this was exposed in 1983 and resulted in fines of hundreds of thousands of Euros to those involved.

It is also unclear if taking a few inches off the horn did anything other than give you an extra thousandth of a second to brace for impact. Bulls are far from precise in their horn swipes, and very often manage to plant the points either sided of a fallen torero. (Photographs on the internet showing horns with the points cut off are deceptive: it is perfectly legal to blunt the horns like this for rejoneo – horse-back bullfighting – to save the horses injury, and in festivals for bullfighting on foot – less formal affairs and usually for charity – as these often take place in plazas where no surgical team is present. ‘Shaving’ and ‘blunting’ are very different procedures from one another.)

As for accusations of doping, any sign of weakness or injury in the bull when he comes out of the gate is jeered and protested by the audience, and if this is upheld by the veterinary advisor who sits beside the president of the ring – with a bullfighting expert, often a former matador, on the president’s other side – the bull is replaced, at full price, by the ring.

A doped bull is an unreliable one, and reliability is the trait most prized by toreros. I’m not saying it hasn’t happened, but the idea of it being common is laughable: all one has to do is watch a few bullfights and one can see the animals are tranquiliser-free. As for claims of rubbing Vaseline in their eyes: every toreros worst nightmare is a bull that does not visually perceive and respond to the movement of the cape but stumbles blindly around the ring goring everything and everyone in sight.

The only way to survive the force of nature that is a fighting bull is to trick it using the evolved flaws in its perceptual and cognitive apparatus, not to remove or adulterate them.

Bulls are expensive, costing up to €5,000 to produce and selling for up to five times that to a first class plaza de toros (there are three categories of plaza, graded by size and amount of use, with nine of the first class – including Madrid, Seville and Pamplona – a few hundred of the second and a couple of thousand of the third. This does not include non-permanent structures called portatiles.)

Obviously, no one wants to incur the cost of replacing a bull, so practices that might lead to that are extremely rare now and, in fact, the situation has been reversed. Once the representative of the bull-ring selects the bulls on the ranch for purchase, their horns are covered with plaster casts to prevent them from injuring and killing one another, as often happens in disputes over herd-dominance. Before selection, though, such disputes are of vital importance as this is how the animals build their battle-hardened musculature and learn how to use the great sabres of horn that spring from either side of their skulls.

The bulls are transported in special trucks and unloaded into corrals with food and water at least a day before to allow them to adjust, before they are paired off – to even the differences, so, big with small, or long horn with short – and the matadors’ representatives draw lots for the pairs at noon on the day of the corrida. They are then put into individual but adjacent darkened chambers to rest them before the spectacle begins. The next time the bull sees the light is on its entry to the plaza, an environment as alien as any other slaughterhouse, and at this moment it is at the height of powers which will only diminish across the next twenty minutes until its death.

* * *

The first of the three acts of the lidia is the most dangerous part of the corrida in terms of the bull’s unpredictability of response, its unregulated charges when it does respond, and its extraordinary energy.

Some twist and turn mid-air like cats, others leap clean out of the ring into the callejón, the ‘alley’ divided from the walled circumference of the sand with a wooden barrier, forming a sheltered space where the toreros can prepare. On a couple of famous occasions bulls have even leapt into the audience itself, mounting hooves on the fence and propelling their half ton weight up and across a ten foot gap into the shocked crowd – if these were drugged it wasn’t with a tranquiliser! (I narrated one of these occurrences for a Bear Grylls’ programme on the Discovery Channel a couple of years back.)

Drugged? Shaved horns? Damaged beyond being a danger?

With this engine of fear and fury, the matador must engage. How much he engages at this stage is down to him, but he must at least walk out with the large capote, ‘cape’, which is distinctively pink on the outside and yellow (or, rarely, blue) on the inside, and is held in both hands. Here begins, or one hopes begins, the dance which is the actual essence of the modern corrida.

Contrary to popular myth, the bull does not react to the colour of the cape but is incited to charge by its movement (the bull has much reduced colour-perception having dichromatic vision – two-colour detecting types of cone in his retina, rather than trichromatic with three types like humans and other primates.)

The matador begins by waving the cape at the bull, and as it charges, the matador’s task is to direct it into its folds which he brings past his body as he rotates at the waist. After the bull passes the man turns around and does the same again. During these exploratory passes the matador makes a decision. If the bull is too wild, tossing its head from side to side as it passes by the man’s body, and the man does not believe he can take control of the bull’s charge, or does not believe it worth the risk to attempt it – the man is injured from a previous corrida, or is tired, or superstitious, or he does not care for the small size or negative temperament of the audience – he will walk away and give up and the horses will enter the ring for the second scene of this act to begin.

The greatest exponent of the two-handed cape today, Morante de la Puebla

However, if the matador’s reaction is a positive one, then you will see him change, and you will begin to see his toreo, ‘the art and science of dealing with bulls in the Spanish manner’, and his own development in the shadow of Belmonte’s innovation, which that master summed up in three words: parar, templar y mandar, ‘stand, temper and send’.

First, the matador must ‘stand’ his ground, planting his feet into the sand and lock his knees rigid. The man does not move, the bull does. The central sculptural aesthetic he imposes on himself is defiance, no matter his inner turmoil. And this is not mere gesture, either. The training of the stance of the legs alone is measured in hundreds of hours in the studio, performing toreo de salón, under the watchful eyes of technical instructors and artistic managers, and studying his own and other matadors’ past performances over and over on film.

The prior general waving of the cape refines into the hecho, the ‘make’. The cape, fifteen pounds of compressed raw silk, is held in finger tips and a flick sent down it so it snaps the base fabric in a way the angered bull is drawn to as surely as a tacked horse is pulled by its reins.

With rigidly upright body, cape flowing out in front, the man makes the bull come to him at a gallop and then draws the cape past his body so the bulls horns’ never touch the cloth – lest it discover this is an empty distraction rather than an actual opponent – nor so far in front it sees the man’s legs and elects to change target. This is to ‘temper’ the charge. At this moment the central aesthetic concept is elegance and suavity of movement, playing counterpoint to the wild ferocity of the dance-partner.

The bull is, anatomically and physiologically speaking, a short sprint animal. It is not a creature of distance and stamina, and after the matador sends it away, it must decelerate hard, turn, and then reaccelerate to killing pace. Usually within four or five of these ‘passes’, it will have slowed and clarified its charge, lost excess vigour and become more considered in its movement as its energetic reserves diminish.

In visual effect to the audience, the deliberate and graceful matador is imposing these same virtues upon his frenzied dance-partner. This, in Spanish, is called dominación, although as much as anything, the way the matador lays the expanse of silk before the great darkness before him looks more like a courtier gesturing for his king to pass him by…

These passes are also judged by their conformity to the set standards of the dance-book of passes. The most basic of these is the verónica, named for the Saint who wiped the face of Christ with a cloth on his way to Golgotha. Toreo may have begun as a most primitive form of art with its cthonically blurred collusion between artifice and reality, but it has grown up in the land of the most ritualised forms of Catholicism. It is no coincidence that good caping is built upon the sixth Station of the Cross.

However, beyond the gladiatorialism and representative reality of man and beast – and the exactitude of tradition and ritual – there is that which makes the perceiving soul, and the performing soul as well, soar. In common with many toreros and aficionados, I believe the greatest matador on the sand today, and perhaps ever, is José Tomás Román.

An elusive figure, José Tomás avoids interviews, the only one I have read being from ten years ago in El País and even then not by a journalist, but by the great flamenco singer Joaquín Sabina. Tomás has banned the broadcasting of his corridas on television since 2000 saying the spectacle only exists in the moment and space of its reality. He has avoided the larger rings of Spain like Madrid and Seville, not least due to their insistence on TV cameras, and will often not appear for years at a time.

José Tomás has achieved something unique among bullfighters in the past half century, which is to marry the highest aesthetic ideals – to be a torero de arte – with the uncompromising approach to the possibility of injury and death of a torero de duros, a fighter of the ‘hard’ bulls from breeders like the legendary Miura family (who remain close friends to this day.)

There have always been aesthetes among toreros who wait for a bull which charges as though mounted on rails, straight and true, and with which they can practise the most beautiful of body postures as the animal glides by – Morante de la Puebla is a great example – but they do not attempt this with more tricky individuals and avoid tricky breeds altogether.

And then there have been gladiators like Juan José Padilla whose still fights despite having had an eye removed along with a portion of his skull by a bull in 2011 (I covered his come back the following year for Condé Nast’s GQ magazine.)

Tomás, however, has no interest in proving himself with hard bulls and has focused on ‘smooth’ bulls from estates that produce straight charging animals. (These tend to be those owned by, or supplied by, the bloodlines of the Domecq family.) However, no estate can guarantee what sort of animal will come out of the gate, and despite this Tomás has fought each animal with which he is presented while insisting on his ideals of art with such vehemence that he either produced the striking beauty for which he strives, or he has been carried out of the ring bleeding. Early in his career it was as often the latter as the former.

In 2010 he reached the zenith of this uncompromising approach when he came within a breath of dying in Aguascalientes in Mexico. The bull’s horn inflicted a wound with three separate trajectories into his body – each of 6 inches in depth – at the junction of leg and abdomen. They breached the femoral, iliac and saphenous arterial blood vessels, which the surgeons could not quickly seal. They poured 14 pints of blood into him – twice his body’s contents – calling the audience for transfusions when they ran out of stock.

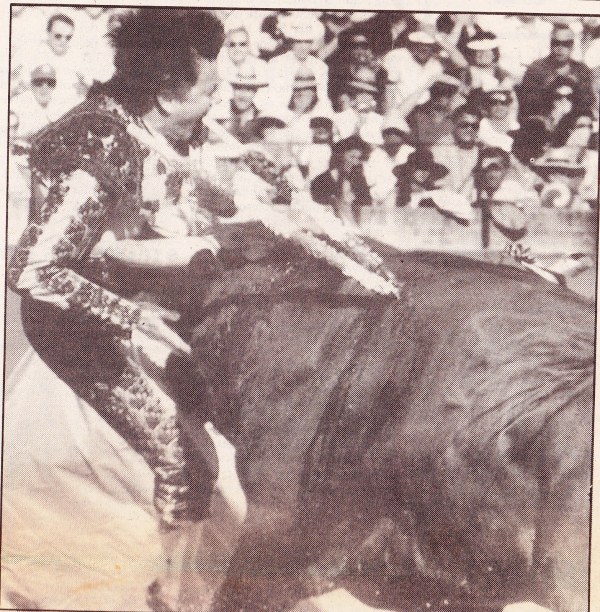

A bloody art-form: José Tomás learning the hard way early in his career

This was how Tomás learned his extraordinary abilities and now when he fights, people leave the plaza de toros in tears of wonder at what they have seen. (This author included, both when I first saw him in May 2009 in Jerez and there again, the last time I saw him in May 2016.)

So what is the nature of this art? To quote that great artist of cinema Orson Welles, who was a bullfighter in Seville as an 18-year-old before he changed artforms to cinema, and whose ashes are now interred at the matador Antonio Ordóñez’s estate in Spain,

What you are interested in is the art whereby a man using no tricks reduces a raging bull to his dimensions, and this means that the relationship between the two must always be maintained and even highlighted. The only way this can be achieved is with art. And what is the essence of this art? That the man carry himself with grace and that he move the bull slowly and with a certain majesty. That is, he must allow the inherent quality of the bull to manifest itself.

* * *

Once this work with the cape – all too brief when it happens, if it happens – is done then the trumpets sound and the horses enter the ring.

‘Act One’ of the corrida is known in its entirety as the tercio de las varas, the ‘third of the lances’, and this second scene explains why. It is also the most controversial and least popular part of the corrida, even among most Spanish audience members.

The heavy horse is armoured with protective padding and ridden by a heavy man wearing leg armour and carrying a lance with a point which projects just less than three inches from a cross-bar. This is the picador.

Around the sand of the plaza de toros are drawn two concentric circles, one within the other, their circumferences separated by two yards of sand. The bull is lured within the smaller circle, while the picador positions himself outside the larger one. Thus a minimum distance is established between the two stationary protagonists, and then the picador ‘cites’ the bull, invoking its charge, by waving the lance above his head, calling, and clanking his armoured boot within his steel bucket-stirrup.

The moment the bull commits to the charge, the picador shoots the lance forward in his hand, locking the haft firm under his arm, aiming the point into the morrillo, the accentuated hulk of muscle resting over the bull’s shoulders that defines the breed and gives it the power of a fork lift truck. (I have seen a bull deadlift a horse and man – specifically a 650kg/1,430lb Percheron-Breton cross horse and a 100kg/220lb man with 35kg/77lb of arms and armour – so all four hooves were off the ground. That’s three quarters of a ton.)

One of the six picadors’ horses preparing at the plaza de toros of Pamplona in 2011. It still works today. (Photo by Alexander Fiske-Harrison)

This part of proceedings is the link to the old corrida, the gladiatorial joust, and today allows the audience to see the power and fortitude of the bull, its ability to ‘take punishment’, to strive against the horse’s padded armour despite the lance-point being within him. This why the lance has a crossbar: to prevent the bull committing suicide on the spot.

This demonstrates the bravura of the toro, and thus its worthiness to be in the corrida in much the same way the torero’s implacability earns him his place. I have seen corridas stopped at this moment by the president of the plaza, and a group of oxen sent in to herd a timid bull away, so it can be replaced with a true toro bravo (needless to say the bull herded out doesn’t get to return to the farm.) The Spanish word bravo with reference to toros comes far closer to its Latin etymological root rabidus, ‘rabid’, than the English sister-word ‘brave’.

Here there is another myth to dispel. Ernest Hemingway opened his 1932 non-fiction book on bullfighting, Death In The Afternoon, thus:

“At the first bullfight I ever went to I expected to be horrified and perhaps sickened by what I had been told would happen to the horses.”

This is because in that first bullfight Hemingway saw – on May 27th, 1923, in Madrid – the horses on which the picador rode would have been either mortally wounded or outright killed by the bull. The plaza functioned as both abattoir for cattle and knacker’s yard for horses at the end of their useful lives. By the mid-1920s this had begun to become an embarrassment to the upper echelons of Spanish society, especially when accompanied by foreign visitors.

This led the greatest breeder of Spanish bulls, the 14th Duke of Veragua – the 1st Duke was Christopher Columbus’s grandson – to request that a French design of padded armour be sent to his estate near Jerez (now belonging to Álvaro Domecq Romero and photographed above) where he displayed its functionality to General Primo de Rivera, the pre-Civil War dictator of Spain. In the summer of 1928 the use of this peto, ‘bib’, was made law. (I wrote on this in more detail for the New York City Club Taurino magazine’s July issue 2016. It is included as an appendices at the end of this essay.)

Although the peto afforded far from perfect protection in the early days, today, speaking as someone who has ridden and studied horses for forty years, in the thousands of ‘actions’ by picadors I have witnessed in plazas around the world in person and on film I have not only never seen a horse killed, but have never even seen one leave the ring lame. This compares with the 200 horses a year who die racing in the UK and 500 in the US. I use horseracing authority figures rather than the absurdly unreliable PETA.

(It should also be noted that it is illegal to drug the horses and their apparently stoic reactions are due to years of training. One can see this in videos online from another great French innovator, Alain Bonijol, who has updated the peto with Kevlar to lighten it and trains his horses to lean into a charging animal using semi-tame bulls on his ranch. You can watch him at work with his much loved and very expensive horses in the video here.)

After a minimum of two pics in a first class plaza or one elsewhere, the president lays out a white handkerchief on his balcony, the trumpets sound – the signal for a change of act – and the picadors leave the ring.

* * *

We now enter Act Two, when the entire pedestrian cast comes on stage.

The bull which we now see in the ring is very different animal. It has been deceived with insubstantial capes into hard charges at immovable objects on which its horns could effect no penetration nor even gain purchase. Its shoulder muscles are punctured, lowering the horns a little, although the blood loss is negligible compared to the sixty or so pints it has within it (the standard veterinary equations for cattle suggest it needs to lose at least a quarter – fifteen pints – before relevant physical or cognitive impairment occurs. Remember, humans can give half that relatively speaking – an eighth of total circulation – one pint – and are still allowed to drive their cars home!)

However, the great expenditure in energy in trying to lift heavy cavalry is what has really taken its toll physically. At a mental and an instinctive level, the inefficacy of the tactics the bull has deployed to this moment has taken its toll: it is confounded. In Spanish its deportment is described as having changed from levantado – elevated, full of power – to parado – stopped.

Now enter the banderilleros, those who place the banderillas – the ‘little flags’ – which are two foot long sticks covered in coloured paper with inch-long steel barbs on the end. Sometimes the matador performs as his own banderillero – notably David Fandila ‘El Fandi’, Antonio Ferrera and the one-eyed Juan José Padilla did this regularly – and historically matadors did so more often than today when dynamic movement rather than static defiance were central to the spectacle. It is immensely popular in smaller, more rural bullrings, and is definitely a thrill to perceive rather than a beauty.

Antonio Ferrera with a bull of Victorino Martín in Seville in 2009 (Photo: Alexander Fiske-Harrison)

The purpose within the development of the lidia of this middle act can be best explained in terms of audience and bull together. The banderillero incites the bull to charge at him by leaping up and down on the spot, arms above his head. In doing this he resembles in silhouette a bull tossing its head in challenge in the distance. Then he begins to run in a manner dictated by how the bull runs in response. The intent here, as with the cape, is to conform to a shape, but here the shape is the path run by both protagonists. At one point on this path – be it head on, poder a poder, or two approaching curves which sketch a bull’s horn in the sand, al quiebro, or the other variants – the torero and toro intersect, and the man thrusts the banderillas’ points into the heavy hide over the bull’s shoulders, before exiting this moment of danger.

The death of a bullfighter: Manolo Montoliú in Seville

Failures at this moment of intersect have huge risks. The last banderillero to die doing this was Manolo Montelui in 1994 in Seville. His “heart was opened like a book” according to the medical report, a grim phrase that also speaks to what the risks to toreros actually are. With a minimum of three surgeons, including general, trauma/vascular and maxillo-facial in the bullrings of the first category, dying requires a straight shot to heart or brain since you are under the knife within a minute. Whereas the 20-year-old novillero, Renatto Motta, who died in May 2016, bled to death during the two hour journey on the road from the plaza de toros of Malco in the Andes to the nearest decent hospital in Nazca.

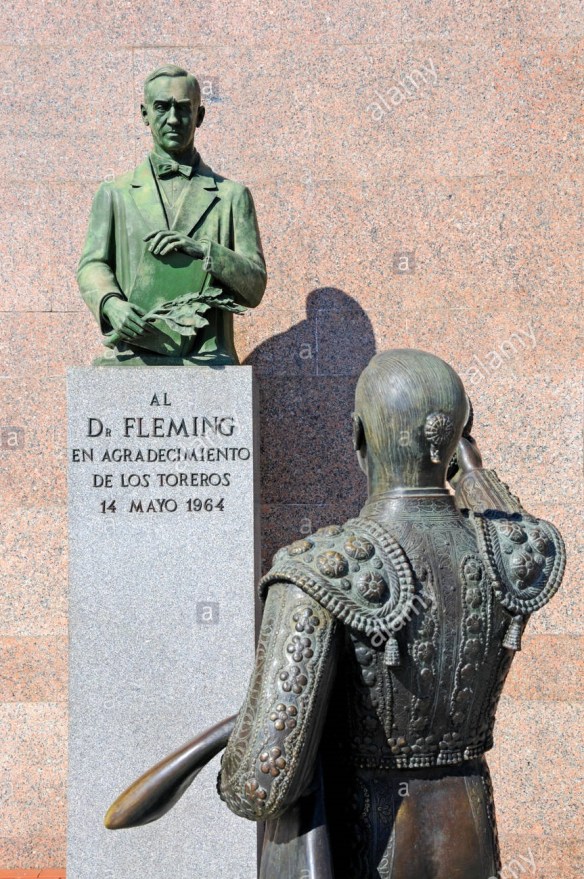

It was these during these movements between hospitals that so many matadors died last century in Spain. That, and from post-injury infection, hence a bust of Alexander Fleming, discoverer of penicillin, stands outside Spain’s largest bullring – the 24,000 seat Las Ventas in Madrid – with a statue of a matador bowing before it.

Movement and risk are central to the tercio de banderillas. It is an athletic pursuit requiring timing on the hoof. It wakes up the audience, the toreros and the toro, as, no doubt, does the fact that the bull comes off each of the three encounters with a pair of mini-harpoons in its shoulders.

Here one must revisit concept of injury and death of an animal for entertainment, in no matter how high- or low-brow a sense of the word entertainment. It requires an almost inhumanly, and some would say inhumanely, open mind to shift one’s perspective if one was born and raised outside bullfighting regions to accept this. Unless, that is, one simultaneously bears fully in mind the fact that we slaughter calves for meat we genuinely don’t need to eat, and do so on the whim of taste. Beef is nutritionally unnecessary, medically dangerous, environmentally damaging and financially punitive. Why do we eat it? For the entertainment of our palates: we eat meat because we like the flavour, pure and simple.

10 July 1994, Plaza De Toros, Pamplona: Bulls’ heads lined up as a worker takes the last side of beef to the waiting truck in the outside the bullring. Photo by Jim Hollander/EPA

Food in the developed world is an arm of the entertainment industry – packaged not to look like the animal it comes from and advertised directly with images that all but claim the beast voluntarily cut its own throat and leapt onto our plates. Almost three million cattle a year are sacrificed in the UK to make this amuse-bouche and more than ten times that number in the US where 78% are factory farmed and do not see the light of day. It is tough to argue that killing an animal for a moment of flavour is right but killing one for art profoundly wrong when the welfare – especially in terms of length and quality of life on the farm – is better in the latter case – and they end up being eaten anyway!

As the philosopher and proponent of Animal Rights, Mark Rowlands of the University of Miami, began his argumentation in his dispute with me in the letters’ pages of The Times Literary Supplement: “the life of a fighting bull is better than that of beef cattle, and death in the ring is no worse than death in a slaughterhouse. Let us accept this premise.”

* * *

Now we come to the final and most famous act, the ‘third of death’, when the matador enters alone with the muleta – the famous red cloth attached to an internal wooden stick – and a sword.

The muleta is a one-handed instrument which may be used in either left or right, whereas the sword must remain in the right. This means that when the muleta is used in the right hand the sword blade is placed in its folds, extending the fabric area to make a considerably larger lure. On the left, the muleta is held only by its internal stick and thus is a smaller distraction and so more dangerous for the matador.

Before Belmonte, the matador made the bull charge with a combination of muleta and his own athleticism, his knees bent and posture crooked like an athlete, ready to get out of the way, his team around him ready to intervene if he was in trouble.

It resembles nothing of what one sees today in the ring, but more closely resembles what you see in the streets when running with bulls.

The change came with Juan Belmonte in 1913. It is often said that Belmonte changed the nature of bullfighting because he was not physically adequate to the athletic task of moving out of the way of the bull and so developed a technique by which he moved the bull instead. Whatever the truth of this theory as a point of origin, there is no denying the static pose and cámara lente, ‘slow motion’ movement which dominates the modern art of toreo owes itself to a single technical accomplishment.

Belmonte stood still and close to the bull so as to place the muleta in its face as that was the only way to make the cloth its sole focus as it charged. He thus not only hid himself from the animal but also gained greater control of its direction as he could determine where within the cloth it was focusing its charge. This led to a further innovation: with the bull thus transfixed, the lowering of the man’s hand leads to the lowering of the animal’s head.

The primary effect of this is the bull must slow down, giving the torero a control he formerly lacked, as well as looking extraordinary to eyes that had never seen this before. Furthermore, on a purely aesthetic level, the bull must arch its neck, making it resemble a horse in dressage, while also creating the body-shape a bull assumes before tossing an opponent. It thus looks simultaneously more controlled and more dangerous, which is a visual conflict, and conflict is the essence of drama.

At the time this was so revolutionary it stunned the audiences who had no idea what they were seeing and made Belmonte a phenomenon. No one working in the old manner could stand this close to the bull time after time and live. Bullfight critics wrote that people should see Belmonte this week as he would be dead next. Guerrita, a master from the 19th century remarked upon seeing Belmonte perform: “the bull that will kill that boy is already eating grass” (i.e. has already been not only born but also weaned.) Belmonte’s great friend and rival, José Gómez, ‘Joselito’, who fought in the old style, said after one particularly famous corrida in Madrid in 1917 in which they shared the ring, “they say that I am the best, and I am. But out there today that man reinvented bullfighting.”

The era in which those two shared the rings of Spain began in 1913 and is called the Golden Age of Bullfighting. It ended in 1920 when against all expectation and augury the classical athlete Joselito was killed by a bull. Belmonte, on the other hand, died by his own volition – suicide by gunshot like his friend Hemingway the year before – not that of a bull in 1962, a week before his 70th birthday.

It is hard to overemphasise how revolutionary this change was. In its absence, the corrida would not have survived the transition to modern Spain as it is the root of all that is visually beautiful in bullfighting and what facilitated its evolution from crude blood-sport to refined blood-art, and allowed the educated elites to defy progressive pressure groups with their claims of barbarism and anachronism. In short, the politicos could say it was Art and believe it.

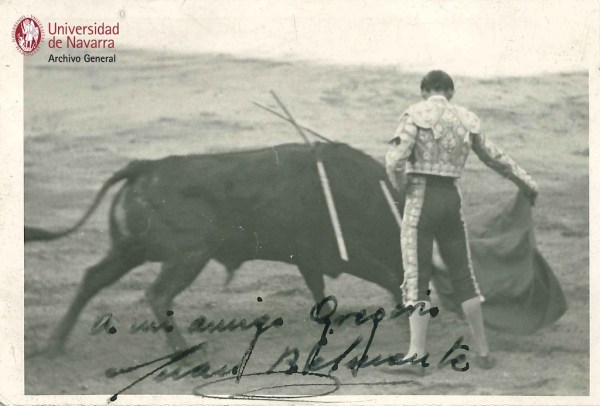

The innovation of Seville, Juan Belmonte (Photo courtesy of the archives of the University of Navarre)

Of course, Belmonte had forerunners in his style – Antonio Montes is the most often mentioned – and there were revolutionaries afterwards. Who it was who began to ligar – ‘to link’, ‘to sew’ – the passes I do not know, but this led to the evolution from ‘the statue and the storm’ (as I titled my paper for the University of Seville’s Foundation Of Taurine Studies) to ‘the dancer in the storm’. It is often said to be the great Manuel Roriguez, ‘Manolete’, a towering figure in toreo from his elevation to matador in 1939 until his death on the horns of the Miura bull in 1947.

Famed for his solemnity and stillness, Manolete became so internationally famous they had to build the largest bullring on Earth, the 41,000-seat plaza de toros of Mexico City, to house his fans.

Where Belmonte faced his cattle three-quarter on, feet apart, Manolete’s stance was in profile, feet together. This makes you less of a target than the cloth but yields a shorter pass as the change of weight from one leg to the other does not move the shoulders as far. However, if you fix the bull into the outside edge of the muleta, you can create a turning arc the bull can complete with less of a pause, allowing a link between one pass and the next, generating a series. This sustains the emotion of the crowd as they view the sculptures of man and animal, moulded by the matador’s mind, and allows it to build, hence the rising chants of olé at each pass, until the crowd are brought to their feet and their cheers torn from the throats by the perfect end of a tanda, a ‘series’.

The solemnity of Córdoba, Manuel Rodríguez, ‘Manolete’ (Photo courtesy of the personal collection of Juan Pedro Domecq)

It can be no coincidence that the linking of separated moments of beauty to generate a moving dance has gone hand in hand with the advent of moving pictures in the ring. Manolete was the first movie-star matador in the Hispanic world.

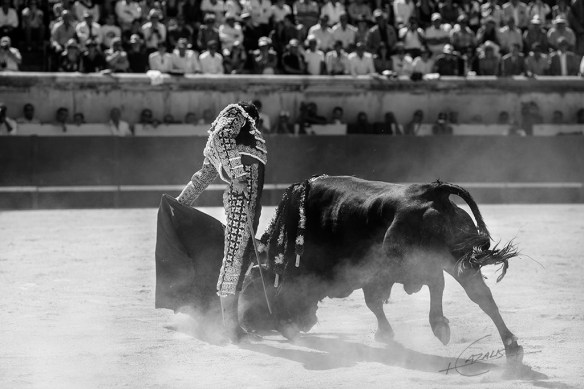

So it is an irony that José Tomás, the matador who took this great stylistic innovator and purified his manner in the ring – as the picture below shows, it is the same pass as Manolete’s, but with an improved line of body and the bull’s horns closer to the leg although it is fixed in the same place within the muleta – went on to ban filming of his corridas, saying true purity lay in the emotions generated for the audience in the ring, not at home on their sofas. As the great contemporary film director Quentin Tarantino has argued again and again, the heights of emotion cannot be achieved in an audience of one.

Of course, in the time of Manolete television did not exist in Spain – it was not launched until almost ten years after his death – and so his performances would have been watched on the giant screen of the cinema sitting among a crowd of aficionados as in the plaza de toros.

The Master from Madrid, José Tomás by Carlos Cazalis, from his book, Sangre De Reyes, ‘Blood Of Kings’

Of the kill itself, although it has become less important relative to the other acts in the ring, it is still a prerequisite, a sine qua non, of a triumph in the ring: to kill badly is to fail. And it is in this moment, the sole moment when the matador charges the bull, entering with the sword volapié, with ‘flying feet’, over the horns and thus exposing his body to them, hence its name: el momento de verdad, ‘the moment of truth’.

The matador lines up the bull with the muleta in his left hand trying to bring the front hooves together to part the shoulders more. He aims the sword point in his right hand, and leaps, trying to find a tiny letter box of a gap between the fourth and fifth, or fifth and sixth ribs, spine on the right, scapula on the left, all made of bone as impenetrable as concrete.

Bullfighter Juan Jose Padilla, who lost an eye in a goring and recovered to fight again, goes over the horns to kill a fighting bull from the Torrehandilla ranch in a bullfight in Pamplona, northern Spain, 14 July 2012, closing the Feria del Toro in the Fiesta de San Fermin. Padilla was awarded one ear for each of his bulls and was carried out of the ring on shoulders. One horn is hitting Padilla in his shoulder and neck area, but he was not wounded. Photo and caption by Jim Hollander / EPA

So that is the bullfight: a scripted drama, whose medium is a dance between the monument to the deliberate, the man, and the incarnation of wildness, the bull, framed in gold and artifice, but whose peroration is a synthesis of the mannered and the real, the ritual sacrifice.

Across the decades the numbers of full corridas has fluctuated massively, usually due to economics and the star quality of the matadors of the time – 1962 had 372 corridas, 1971 had 682, 1981 only 390, 2007 was the historic pinnacle of 953 and last year 412 – however, it seems unlikely it will disappear any time soon. It is more than just men – and some women – torturing bulls to death while facing a more limited risk themselves, a sort of daredevil recklessness for the thrill of cruelty. To end with the words of the author one this subject one tries so hard to avoid, Ernest Hemingway:

Any man can face death, but to bring it as close as possible while performing certain classic movements and do this again and again and again and then deal it out yourself with a sword to an animal weighing half a ton which you love is more complicated than just facing death. It is facing your performance as a creative artist each day and your necessity to function as a skilful killer.

APPENDIX:

Magazine of the New York City Club Taurino

June – July 2016

All The Pretty Horses

“At the first bullfight I ever went to I expected to be horrified and perhaps sickened by what I had been told would happen to the horses.”

So begins the English-language bible on bullfighting, Ernest Hemingway’s Death In The Afternoon. Of the three acts of the bullfight, the first – or more specifically Act One, Scene Two – has always been controversial, but used to be much more so.

When Don Ernesto first went to a bullfight in Madrid on May 27th, 1923, the horses on which the picador rode would have been mortally wounded if not outright killed by the bull.

When Don Ernesto first went to a bullfight in Madrid on May 27th, 1923, the horses on which the picador rode would have been mortally wounded if not outright killed by the bull.

The great breeder of bulls, the late Juan Pedro Domecq, argued in his 2010 book Del Toreo A La Bravura, that the technique of the picador was to fend the bull off the horse using the lance. However, either this was always an ideal rather than a reality, or the ‘third of the lances’ fell into a rather shocking decadence, because by the mid-19th century the number of horses a bull killed was used as a direct measure of its bravura. (Bravo in Spanish with reference to toros is much closer to its Latin etymological root rabidus, ‘rabid’, than its English linguistic cousin ‘brave’.)

The taurine journal El Enano reported that during the bullfighting season of 1855, although only 191 bulls had been killed in the plazas that year in Madrid, 412 horses had been killed on the horns of them. Some sources give the Spanish national average as being as many as three horses per bull. The plaza de toros functioned not only as abattoir for cattle but a knacker’s yard for horses as well.

By the mid-1920s when Hemingway first came to Spain, this had become an embarrassment to the upper echelons of Spanish society, especially when accompanied by foreign guests.

One legend has it that the then Prime Minister of Spain, General Primo de Rivera, was at a corrida in Aranjuez in the spring of 1928 accompanied by a foreign woman who was romantically linked to a French government minister. They sat barrera and she watched in horror as a bull eviscerated a horse in front of her, which then proceeded to gallop around the ring trailing “the opposite of clouds of glory” as ‘Papa’ phrased it. The General demanded something be done.

One legend has it that the then Prime Minister of Spain, General Primo de Rivera, was at a corrida in Aranjuez in the spring of 1928 accompanied by a foreign woman who was romantically linked to a French government minister. They sat barrera and she watched in horror as a bull eviscerated a horse in front of her, which then proceeded to gallop around the ring trailing “the opposite of clouds of glory” as ‘Papa’ phrased it. The General demanded something be done.

Meanwhile in France, things had been taken a step further by Jacques Heyral, a young man with a gift for matters equine from outside Nîmes, in the South West of France, a city with a famous 1st Century A.D. Roman coliseum which had been restored to use as a bullring in 1863.

Returning from the First World War, in which Heyral had survived the horrors of Verdun because he was posted to look after the officers’ horses, he was put in charge of the picadors’ horses at the place des taureaux and began designing armour to save the lives of the animals who had saved his in the trenches.

By 1927 Heyral had a functioning leather caparison, an equine coverlet, to protect the horse, which became standard in France and thus well-known to the Spanish picadors who came with their matadors to the major bullrings of Southern France.

This was not necessarily out of kindness, by the way. The daily task of a picador in Spain up until then was to try to dismount from a dying horse without being thrown or being pinned beneath it. And even then they were left standing in heavy leg armour with no cape in front of a bull. Anything that changed this state of affairs would have been popular to say the least.

For this reason the greatest breeder of Spanish bulls of the time, the 14th Duke of Veragua – the 1st Duke was Christopher Columbus’s grandson –requested that a caparison be sent to his ranch Los Alburejos near Jerez de la Frontera, a ranch that now belongs to Álvaro Domecq where he breeds the Torrestrella bulls.

There he showed it to General Primo de Rivera in a tíenta in the spring of 1928, and by that summer its use was made law by Royal decree. In Spanish it was called the peto, or ‘bib’, since the prototype covered mostly the chest.

Does the modern peto work? Although not faultless, especially in the early days, having ridden and studied horses for thirty years, and seen the thousands of ‘actions’ by picadors in person and on film, this author has not only never seen a horse killed, but has never even seen one leave the ring lame.

(It should also be noted that it is illegal to drug the horses and their apparently stoic reactions are due to years of training. One can see this in videos online from another great French innovator, Alain Bonijol, who has updated the peto with Kevlar to lighten it and trains his horses to lean into a charging animal using tame bulls on his ranch.)

And if you go to Nîmes, you can see Jacques Heyral’s grandson Philippe in the callejón, where he runs the patio de caballos today, still looking after the horses that saved his young grandfather’s life and are the reason he is alive today.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison’s short story ‘Les Invincibles’, set in Paris in 1958 and Pamplona in 1959, was a finalist for Le Prix Hemingway International, awarded in Nîmes in May, and was be published as part of Uriel: Et autres nouvelles du Prix Hemingway 2016 by Au Diable Vauvert in French.

ALEXANDER FISKE-HARRISON

THIS COMMENT WAS PUBLISHED IN ORDER TO POINT OUT THE FALSE STATEMENTS WITHIN IT, PARTICULARLY WITH REGARDS TO FRENCH LAW. SEE MY COMMENT IN RESPONSE. AFH

Dear Sir,

Re: Your article “An Essay on Bullfighting”

As a French citizen, I would like to draw your attention to your assertion that bullfighting is legal in southern France: it is simply not so.

Two articles of our penal code (art. 521-1 and 522-1) make it clear that its cruelty makes bullfighting a crime which can send its perpetrators behind bars.

Therefore, it is sheer propaganda from the business of bullfighting to present the fact that toreros are indeed never prosecuted in southern France as proof of the local legality of their cruelty: the truth is that art.521-1 both makes it a crime AND, at the same time and in the name of tradition, requires justice in southern France to look the other way and not punish it.

In short: though it is ILLEGAL, corrida is locally TOLERATED.

J hope you will agree to correct the error you were unwillingly led to make yours.

Thank you for reading this.

Best regards

Rose Chaplain

Ms Chaplain,

I have published your comment in order to point that not only is it false in its presentation of so-called legal ‘facts’, but is also an attempt at the very same dishonest and/or erroneous propaganda it claims to be fighting against!

The French penal code you cite is quite clear in its direct statement that it is does not apply to bullfighting.

“Les dispositions du présent article ne sont pas applicables aux courses de taureaux lorsqu’une tradition locale ininterrompue peut être invoquée.”

“The provisions of this article are not applicable to bullfights when an uninterrupted local tradition can be invoked.”

The law can be found on the French government’s website here: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/article_lc/LEGIARTI000044394119

Bullfighting is not, as you say, ‘illegal but tolerated’, but instead is perfectly legal where it is practised in France.

It is untruths like this that led me to research and write this essay in the first place.

Yours,

Alexander Fiske-Harrison

Dear Mr Friske-Harrison,

I can’t imagine you are serious when you imply that French lawmakers could have stated that the cruelty of bullfighting is no longer cruel when practiced in southern France!

It seems that you are overlooking a “detail”: nowhere is it said that “this ARTICLE is not applicable to corrida”, which would indeed leave the cruelty of corrida out of the sphere of illegal activities, but that the “DISPOSITIONS” (i.e. the penal consequences) corrida normally entails won’t apply in southern France.

You’ll find proof of this right after Art. 521-1, in Art.522-1,

https://vu.fr/pBnkh

the first sentence of which reads:

“Le fait, sans nécessité, publiquement ou non, de donner volontairement la mort à un animal domestique, apprivoisé ou tenu en captivité, HORS DU CADRE D’ACTIVITES LEGALES , est puni de six mois d’emprisonnement et de 7 500 euros d’amende.”

If, as is killing bulls in a slaughterhouse, bullfighting was legal, it would simply not be concerned by the penalties, and there would have been no need for a second sentence that specifies that

“Le présent article n’est pas applicable aux courses de taureaux” (This article is not applicable to bullfights) !

I hope that, in the same way you published my initial comment ” IN ORDER TO SHOW THE LENGTHS OF FALSE PROPAGANDA SOME WILL GO TO”,

you will be honest enough to publish my answer to the accusation you wrongly and offendingly brought against me.

Best regards

Rose CHAPLAIN

Post-scriptum: Further my earlier comment, I have had the misfortune to receive further correspondence from Ms Chaplain where she tries to claim I am hiding the truth, despite including the link to the law I quote on the French government’s own website of its laws, and further claims that despite the corrida being specifically named as being exempt from application of the law in question in the Republic of France, she claims it is still illegal under her personal interpretation of the law. This despite the French Consitutional Court upholding the status of bullfighting as legal in 2012, and a bill being debated in the French parliament which would de jure remove the exemption from illegality for the corrida in certain places in France, thus de facto banning the spectacle.

If the legal status were not clear enough in the composition of the law, the subsequent court judgment and legislative debate certainly hammer home to all but the most deluded of minds the present legal status of the corrida in those places in France with an uninterrupted historical tradition of it: It is completely legal and is actually regulated and security for it provided by the police, both local and national, and the courts.

Anyone who tries to tell you otherwise is lying, both to you and themselves. Ignore and block them. Life is too short to keep company with ignorance and deceit. AFH