My article about bullfighting and my book, Into The Arena, appeared in the Daily Telegraph yesterday (online here). However, it was edited to two-thirds of its original length, mainly to save money on photos it would seem. Here is the original.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison

Why I shouldn’t win the ‘Bookie’ Prize

Alexander Fiske-Harrison, on why his shortlisted book Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bullfight should not win the William Hill Sports Book Of The Year Award 2011

A life and death matter: Alexander Fiske-Harrison (far right) running with the bulls in Pamplona, Spain Photo: Reuters /Joseba Etxaburu

When my publisher told me that my book was longlisted for a sports writing prize sponsored by William Hill – the Bookie Prize as it is known – I smiled a cynical smile. Controversy equals publicity, I thought, and this little gambit had a timely ring to it, given that it came less than a week after the Barcelona bullring had its last ever fight before a Catalonia wide ban on the activity came into force. Something often reported here as “Bullfighting Dies In Spain”, even though of the thousand bullfights a year, less than a dozen were held there.

In Spain itself bullfighting is written about in the cultural pages of the newspapers, not their sporting section and 2011 not only saw its regulation transferred from the Ministry of the Interior to that of Culture, but over the border in France it was placed on the list of the “cultural patrimonies” making it effectively unbannable. (French bullfights are mainly in the south, most notably in the restored Roman colisea of Arles and Nîmes.) Even Ernest Hemingway, the most famous writer on the subject in English wrote in Death In The Afternoon: “The bullfight is not a sport.”

So, whilst grateful for the nod, I didn’t think any more of it. However, when I found myself on the shortlist of just seven books, I wondered to myself what I would say if I received the prize and was then asked the inevitable question, “is it even a sport?”

The answer is easy: no. It is so much more than a sport. Even the dubious phrase “field” or “blood” sport, namely hunting, shooting and fishing, is inapplicable (whatever the League Against Cruel Sports say.) I can say this with authority because I spent two years in Spain studying it, not just from the stands, but from the sand too: cape in hand, a third of a tonne of bull trying to kill me, although in the end, it was I who killed it.

Originally, my plan was quite different. My book proposal said that I wanted study this strange Spanish pursuit from an impartial perspective. I had studied biology and then philosophy as an undergraduate and postgraduate, and have been a paid-up member of the WWF for more than two thirds of my life.

However, I slowly came to understand that if you are serious about welfare then the fighting bulls’ lot of five years on free-release followed by twenty-five minutes in the arena is equal if not better than the meat cow’s life of eighteen months corralled in prison followed by a “humane” death.

As for the argument that killing for food is not the same as killing for entertainment, I am afraid that it is exactly the same. Except in certain dire circumstances, which are never the case in modern Britain, we eat meat because we like the taste, i.e. to entertain our palates. More often than not, with obesity rates as they are, it actually has a nutritionally negative value.

And as for the argument that watching a living creature’s unsimulated death is somehow a sin: Is anyone seriously claiming the astonishing success of the BBC’s Natural History Unit is because we all want to learn a little more biology rather than replicate the thrills of the Circus Maximus in the name of conservation?

It was not long before I started to see the beauty of toreo – bullfighting as a word does not exist in Spanish, and in English comes from our artless, riskless and brutal hobby of bull-baiting. It is for beauty that the real aficionados attend the corrida, not for pomp, not for thrill, and certainly not for blood. The bullring atmosphere in my adopted city of Seville is silence until beauty appears. This is usually in the final and most famous of the three acts of the fight, the “Third of Death”, in which the matador passes the bull with a red cape, as closely and as elegantly as he can, while the only chant you will hear is that of “olé” at each pass.

And don’t take my word for this. Here is what another English-speaking fan of the corrida – and no mean artist himself being producer, director, writer and lead actor of Citizen Kane – had to say on the matter:

“What it comes down to is simple. Either you respect the integrity of the drama the bullring provides or you don’t. If you do respect it, you demand only the catharsis which it is uniquely constructed to give. And once you make this commitment you are no longer interested in the vaudeville of the ring. You don’t give a damn for fancy passes and men kneeling on their knees. There used to be this fraud who bit the tip of the bull’s horn. Very brave and very useless, because it played no part in the essential drama of man against bull. Such tricks cheapen the bull and therefore lessen the tragedy. What you are interested in is the art whereby a man using no tricks reduces a raging bull to his dimensions, and this means that the relationship between the two must always be maintained and even highlighted. The only way this can be achieved is with art. And what is the essence of this art? That the man carry himself with grace and that he move the bull slowly and with a certain majesty. That is, he must allow the inherent quality of the bull to manifest itself.”

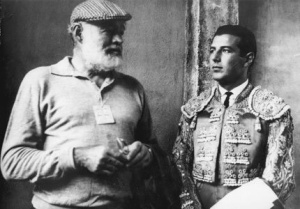

I too came to understand what Orson Welles – who also trained as a torero – had come to understand before me, as had his friend Hemingway before him. Closer to home, the theatre critic and first ever literary manager of the National Theatre, Kenneth Tynan, wrote of the “slow, sad fury of a perfect bullfight,” comparing it to Shakespeare’s Othello in its dark majesty and gravity.

At the same time, I became friends with some of the matadors, like the larger than life figure of Juan José Padilla, who fought the most dangerous bulls of all, the Miuras. This breed has killed more matadors than any other. Today, Padilla is in hospital, a bull having taken away the sight in his left eye, and paralysed that side of his face, in a goring so gruesome the image circulated around the world.

Another friend who stills fights is Cayetano Rivera Ordóñez, grandson of the great Antonio Ordóñez about whom Hemingway wrote the book, The Dangerous Summer, and at whose house Welles’s ashes are interred. Cayetano’s father, Paquirri, had a less fortunate career, being killed by a bull in 1984.

It was these two who encouraged me to venture into the ring so I could write about their world with an understanding that transcended the appreciation of the beauty. Instead of just spectating, I came to know the tension, the fear and the injuries suffered by these artists. Of course, what I managed with a three year old bull was but a childish copy of the sculptural forms they generate as they manipulate the black thunder that bears down on them. (See the difference between the photos of Cayetano me both performing naturales.)

Looking at the other books on the shortlist – a young rugby player tragically paralysed, a goalkeeper driven to suicide by depression, a cyclist driven to take performance enhancing drugs – one can see there is much in common with the troubled life of toreros. And when I describe in the penultimate chapter of my book mapping my daily five mile runs to include every water fountain in Seville’s public parks to prevent heatstroke in the 110 degree heat, or re-tearing the meniscal cartilage in my right knee while doing wind-sprints in the week of my big fight, the athletic aspects are clear.

However, when I speak of the bullfight being the only art-form which both represents something and just is that thing at the same – the matador’s elegant immobility in the face of the bull not only represents Man’s defiance of Death, it is a man defying death (and there are women who do it too, such as the rising star Conchi Rios) – it becomes clear that there is more here than mere sport. It is no “game” that you see Padilla involved in the photo enclosed. I remember that day well, for I was in the ring too, although not with the giant bulls that took him from being a baker’s apprentice in poverty-stricken Jerez, to the heights of fame in the “Cathedrals of Toreo” – Seville and Madrid – and then took it all away again. My ambitions and my achievements were much less.

Love it or hate it, bullfighting is not a sport. To devotee and animal rights activist alike, it is much, much more important than that.

P.S. I see that the Independent in Sunday has published its sports journalist Simon Redfern’s trite little trashing of my book. In response I will only say that (1) I wish I had been a friend of Cayetano Ordonez, but he died a decade and a half before I was born and (2) that the Indie still owes me my fee FIVE months after publishing an extract from this self-same trashed book, back when they thought I was an “the acclaimed British writer” (see here). Double standards anyone? AFH

Pingback: – The Last Arena