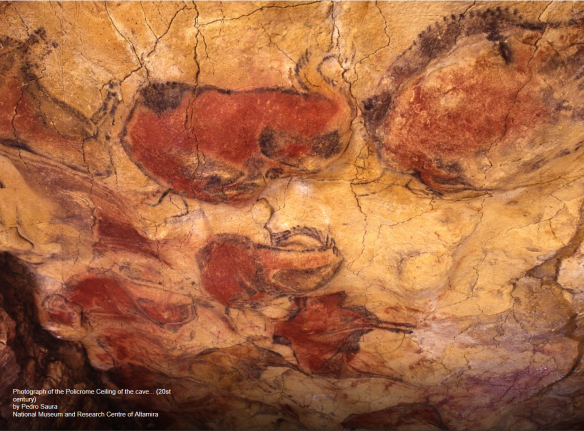

Yesterday Google opened its page with an image from the Cave of Altamira, the oldest known art, painted on walls deep underground in Cantabria, northern Spain. (I have written about them in more detail in my chapter on the history of the region in the recent book The Bulls Of Pamplona.)

Yesterday Google opened its page with an image from the Cave of Altamira, the oldest known art, painted on walls deep underground in Cantabria, northern Spain. (I have written about them in more detail in my chapter on the history of the region in the recent book The Bulls Of Pamplona.)

This is the 150th anniversary of the rediscovery of those caves, suitably a wandering hunter, and the institute which manages them has just launched a new exhibition to better educate the people of today about a range of artworks which began 36,000 years ago.

The subject of this art, the first Art – like the subject of the life of its rediscoverer – is the hunt, and Man’s first confrontation with those intertwined concepts of Nature and Death and how we inflict the latter upon the former in order to sustain ourselves against both.

Man kills to live, and thus lives in the shadow of Death, his own and that of others. Our first religious instincts come from here, thus the ritualistic nature of the hunting scenes upon the walls.

The first hunters – like all good hunters today – are humble and venerate the animals they kill, even as they defy their attempts to do the same to us. There is contradiction there, and as there always is when humans encounter contradiction, there is a ritual manner to quieten the troubling questions raised.

So it is an irony that on the same day we celebrate thirty-six millenia of art, a Spanish party of the political extreme, Podemos – the Left in this case – is offering to use that bane of modern populist politics, the referendum, to censor it. In particular one of its more arcane and archaic instantiations, and the one that is most singularly Spanish, bullfighting.

As I have written in these pages before, bullfighting is an English word, not a Spanish one, but is co-opted from its original use as an alternative to bull-baiting, i.e. setting dogs on a tethered animal. La corrida de toros actually translates as ‘the coursing of bulls’ – coursing being to hunt at a run – showing the historic origins of that which is now almost pure art and ritual, an aestheticized rite that ends in a sacrifice.

The art of the matador José Tomás, regarded by many as not only the most artistic torero alive today, but in history. This photo was taken during a historic corrida in Nîmes, France, in 2012 by Carlos Cazalis, and forms part of his book Sangre de Reyes, ‘Blood of Kings’

(N.B. All bullrings are EU-registered slaughterhouses, their products ending in the food-chain, as with all the world’s 1.3 billion cattle)

However, rather than recite my own views once again, or even to give the excellent public riposte of Victorino Martín in the newspaper El Mundo, himself a famed bull-breeder and president of la Fundación del Toro de Lidia, ‘the Foundation of the Fighting Bull’, which includes the perfectly apposite comparison:

One remembers all too well the actions of the Taliban upon the Buddhas of Bamiyan, destroyed because for failure to fit into their moral canon. Pablo Iglesias [leader of Podemos] considers the bulls morally wrong, so he proposes a referendum to end them.

It was precisely to avoid these things that UNESCO approved conventions such as the Cultural Diversity of 2001 and of which Spain is a party, which seeks to protect all cultural expressions against fundamentalisms…and if Podemos is tempted to say that “is that bullfighting is not culture”, UNESCO is already ahead of them, explaining that the only limit when considering when a culture is inadmissible are human rights and fundamental freedoms. I repeat, human rights …

I offer instead the words of someone from the other side of the debate, an author who defines himself as both of the Left and as anti-bullfighting, but who – unlike the narrower political minds of Podemos – took up the Foundation on its offer to at least witness what he stood against. His fascinating essay on his reactions is translated.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison

Continue reading