Padilla at home (Photo Zed Nelson/GQ/Condé Nast 2012)

It was the last bullfight of the Spanish season, held, as it has been for centuries, in the 250-year-old plaza de toros in Zaragoza in north-eastern Spain.

Juan José Padilla, a 38-year-old matador from Andalusia in the south, was fighting the fourth bull of six (he’d also fought the first.)

The bull, ‘Marqués’, was a 508kg (1,120lb) toro bravo born 5 years and 8 months previously on the ranch of Ana Romero, also in Andalusia. Before entering this ring it had lived wild, ranched from horseback, and had never before seen a man on the ground.

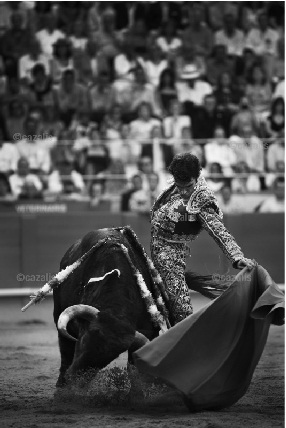

Padilla passing a bull with the magenta and gold two-handed capote, ‘cape’ (Photo: Alexander Fiske-Harrison)

Padilla was midway through the second of the three acts of the spectacle. He had already caped the bull with the large, two-handed magenta and gold cape, the capote, then the picador had done his dirty work with the lance from horseback, tiring the bull and damaging its neck muscles to bring its head down.

Now Padilla, rather than delegate to his team as other matadors do, was placing the banderillas himself, the multi-coloured sticks with their barbed steel heads. He had put in two pairs and was on the third. He ran at the bull with a banderilla in either hand, it responded with a charge, Padilla leapt into the air, it reared, he placed his sticks in its shoulders and landed.

Juan José Padilla ‘places’ the banderillas (Credit: WENN US / Alamy Stock Photo)

Running backwards from the charging bull, his eyes were focused on the horns coming at him in an action he had performed tens of thousands of times before. However, this time his right foot came down slightly off centre and in the path of his left, foot hit ankle, and then he was down.

In a breath the bull was on him and its horn took Padilla under his left ear, cracking the skull there, destroying the audial nerve, and then driving into the jaw at its joint. It smashed up through both sets of molars and ripped through muscle and skin before exploding his cheek bone as surely as a rifle bullet, stopping only as it came out through the socket of his left eye – from behind – taking his eyeball out with it, shattering his nose and then ripping clean out of the side of his head.

There is an image I will never lose, much as I wish I could. It is of a man standing with half his face held in his right hand. Cheek, jaw and eyeball, like so much meat, resting in his palm as he walked towards his team uncomprehending, and they, with looks of absolute horror, grabbed his arms and rushed him to the infirmary of the ring.

The second worst image

And yet here, in the amongst the carnage inflicted on a human body by a half ton of enraged animal, is the key to Juan José Padilla. The clue is in the phrase “stood up.”

Soccer players are stretchered off the field from a tap to the ankle. Boxers go down from a padded glove. This was more than half a ton of muscle, focused into a pointed tip that ploughed through his skull like a sword through snow. And the man got up and walked.

Then came coma and intensive care and surgery after surgery. Continue reading